macOS Catalina & Osquery

I'm sorry Dave, I can't let you query that...

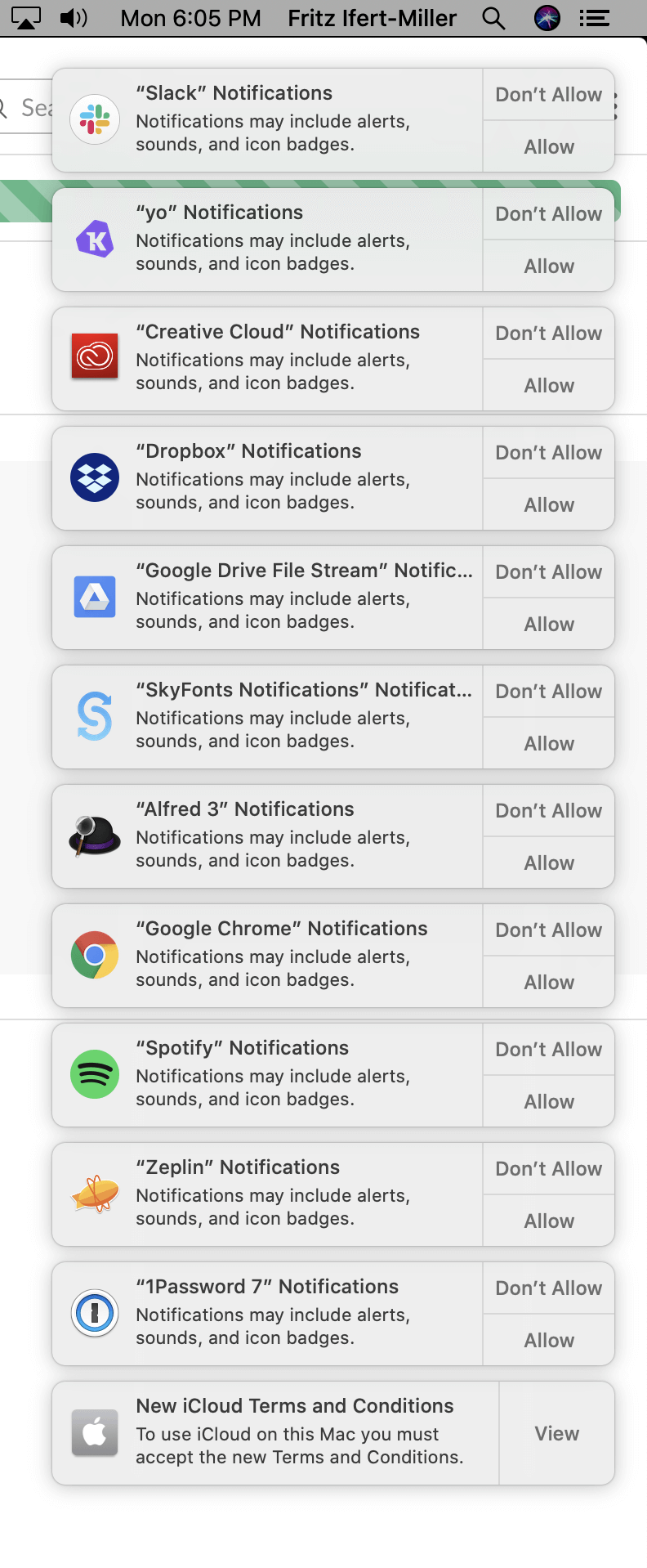

With the release of macOS Catalina, Apple has overhauled its user privacy model, a road they have been on since Mojave. Starting with macOS 10.15 (Catalina), file directories that belong to a user (eg. Downloads, Documents, Desktop, etc.) will require explicit permission to be accessed by your Apps.

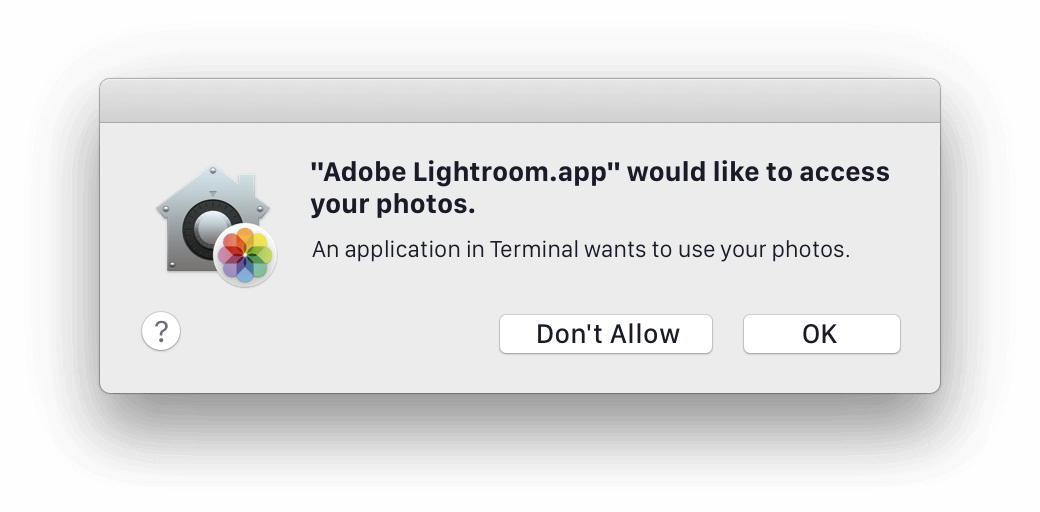

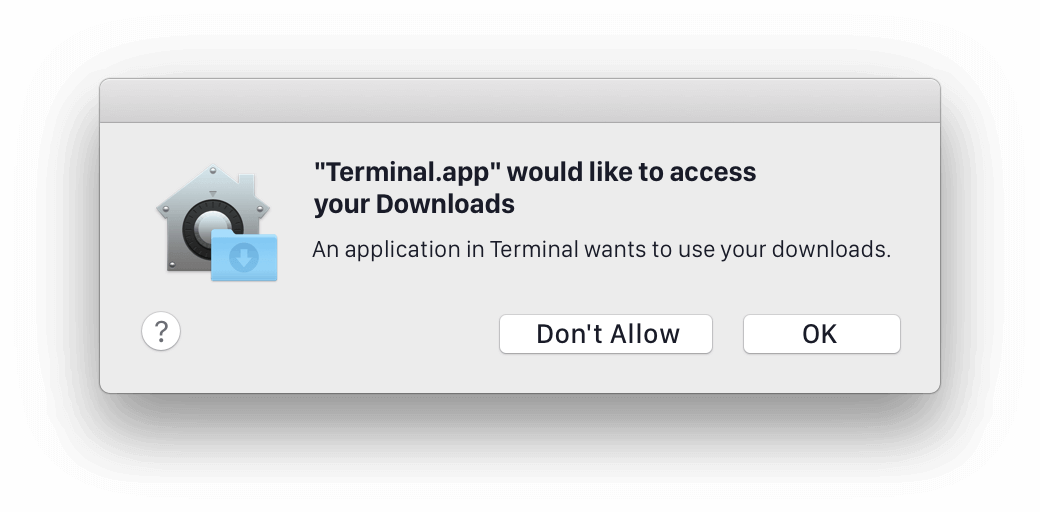

Want Adobe Lightroom to catalog the contents of your ~/Pictures folder? You’re gonna need to authorize that:

Want to open and edit a downloaded config file with nano? You guessed it,

authorization necessary!

Which means you can no longer use osquery to enumerate the contents of any User-spaced folder on a device, for example:

SELECT * FROM file where directory = '/Users/fritz/Downloads/' AND filename LIKE '%database_export%'

Catalina Privacy = Windows Vista UAC v2?

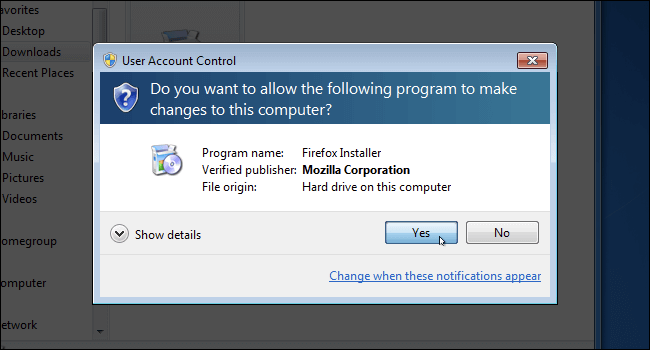

Users lucky enough to remember the briefly lived replacement to Windows XP: Windows Vista, will likely recall the hundreds of times they saw a screen which looked like this.

Collectively, these pop-ups were viewed with frustration and disdain by users. They felt intrusive and disruptive to the task you were trying to accomplish, but this UX didn’t spontaneously generate. The folks in Redmond were trying to address a real issue. Without adequate disruption, users don’t consider their actions until it’s too late. Without this virtual chicane, it can be a high-speed straightaway to malware installation.

Though it feels like a UX anti-pattern, slowing down a user, is often the best way to make them think.

That being said, the initial Catalina experience feels mired with these permission prompt speed-bumps. Especially when they break the basic functionality of Apps which previously required no action from the user.

Upgrading will require some degree of patience on the part of both the end-users and administrators who support them. For both it’s important to understand how these permissions are set, modified and stored in macOS Catalina, which is largely via something called TCC.

TCC and Me: the macOS permissions model

This overhaul to Privacy on macOS may feel jarring to some but it has actually been a long-time coming. Transparency, Consent, and Control (TCC) was introduced by Apple in OS X all the way back in 2013 (10.9 - Mavericks). TCC promised users a method to introspect and granularly grant permission to their private data. With each subsequent major OS release, Apple has expanded the number of permission scopes, and tightened the screws on its default policies.

Catalina represents a logical step forward in Apple’s initiative to protect user’s data from being shared with 3rd parties.

+------------------------+------------------------+

| OS X 10.10 (Mavericks) | macOS 10.15 (Catalina) |

+------------------------+------------------------+

| Location Services | Location Services |

| Contacts | Contacts |

| Calendars | Calendars |

| Reminders | Reminders |

| Twitter | Photos |

| Facebook | Camera |

| Accessibility | Accessibility |

| Diagnostics & Usage | Microphone |

| -- | Speech Recognition |

| -- | Input Monitoring |

| -- | Full Disk Access |

| -- | Files & Folders |

| -- | Screen Recording |

| -- | Automation |

| -- | Analytics |

| -- | Advertising |

+------------------------+------------------------+

The permissions added represent a clear push towards protecting user’s privacy and giving them the ability to limit access to their data.

Managing TCC on macOS

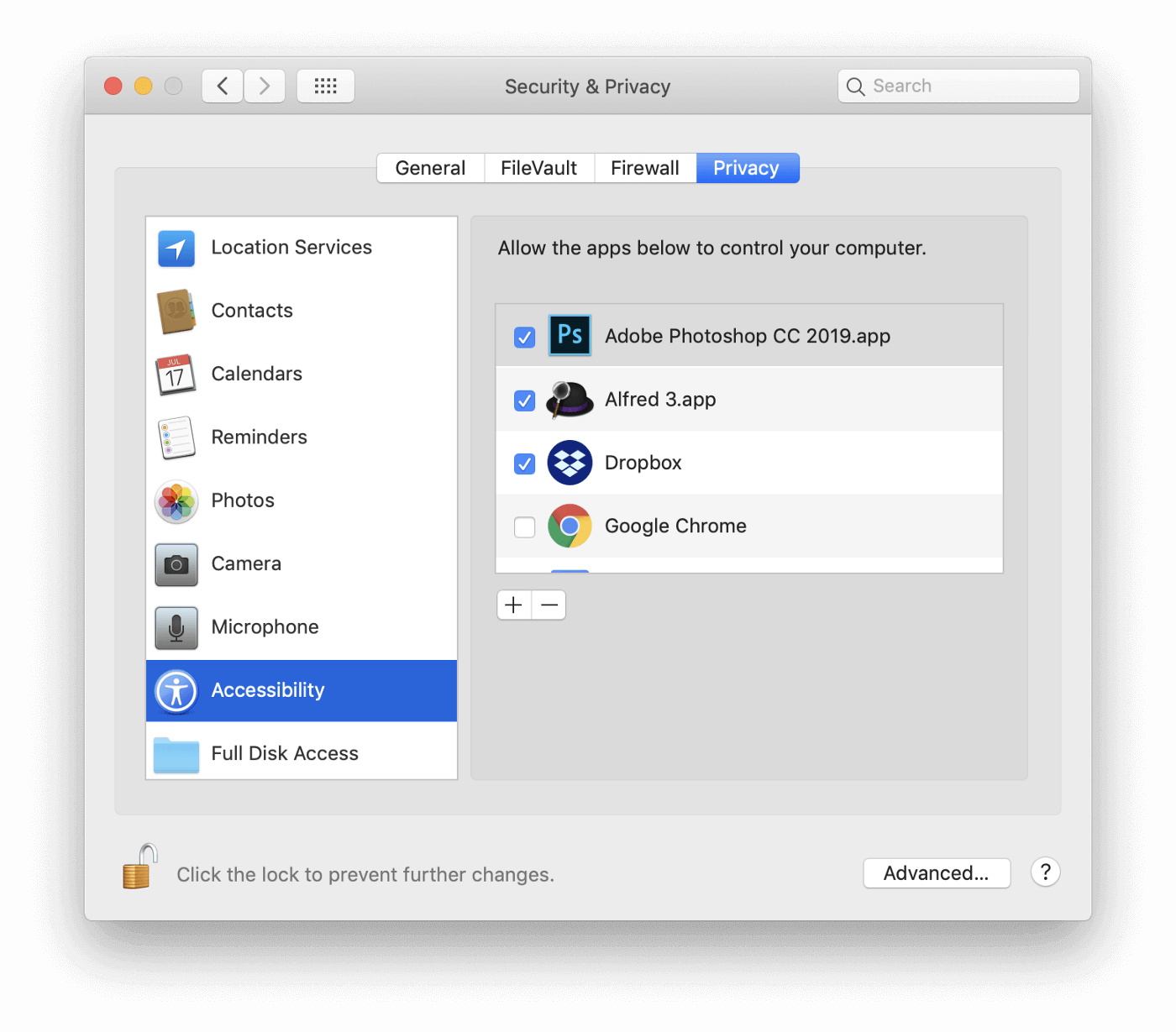

TCC is controlled almost exclusively through the OS System Preferences GUI.

Though a command-line tool exists: tccutil, it can only be used to “reset”

(clear) an app’s permissions. Not to add a new app or elevate an existing one.

Apps permissions are scoped to the various resource they interact with (Photos, Camera, Location Services, etc.)

TCC under the hood

TCC is managed on the system level with two SQLite databases stored in both system-space and user-space.

These permissions are stored in two locations:

root: /Library/Application Support/com.apple.TCC/TCC.db

The root location tends to contain the bulk of 3rd party applications requesting elevated permissions.

user: /Users/username/Library/Application Support/com.apple.TCC/TCC.db

The user locations appear to contain many of the default installed apps on a macOS device which have been hardened by Apple. There are other user configured items however.

Clever users might see an obvious method to introspect and modify TCC

permissions, storage of TCC rules in a SQLite database should make interacting

with TCC no problem. In the past, you could issue INSERT commands via the

terminal to add new authorized apps:

sqlite3 /Library/Application\ Support/com.apple.TCC/TCC.db "INSERT INTO access VALUES('kTCCServiceAccessibility','<APP>',0,1,1,NULL,NULL);"

When a loophole exists, you can expect abuse will result in it being closed. Which is why in the release of macOS Sierra Apple locked access to the TCC.db file via SIP (System Integrity Protection) partially in response to misuse by the DropBox team.

While it’s great that applications cannot adjust the configuration of TCC directly, it has the consequence of preventing users and admins from reading the TCC.db file as well. If a system-administrator wants to monitor permission authorizations and configurations of TCC settings they have no means of doing so outside of physical admin access to the device or through the installation of an MDM profile on DEP enrolled devices. Unless…

TCC and the Full Disk Access Permission

There is one way to inspect the contents of TCC.db: by granting an application the permission for: Full Disk Access

This permission should not be granted lightly, and should be reserved for trusted applications that have a very good reason for needing it.

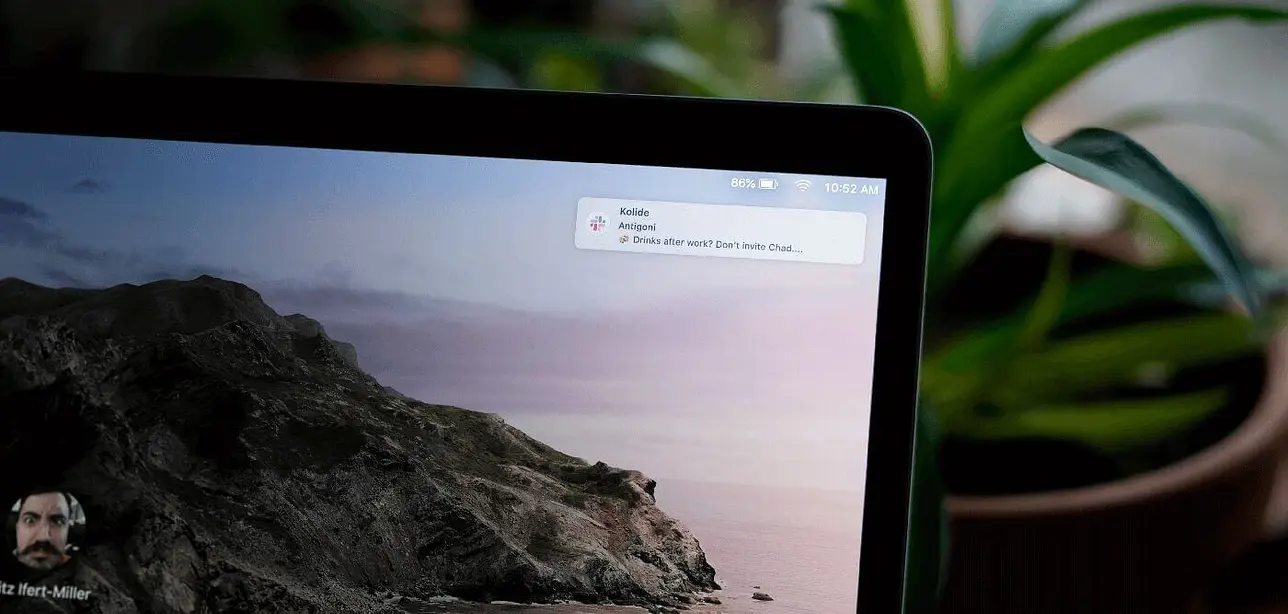

In the case of osquery and Kolide, this permission is necessary to permit queries to run within User directories.

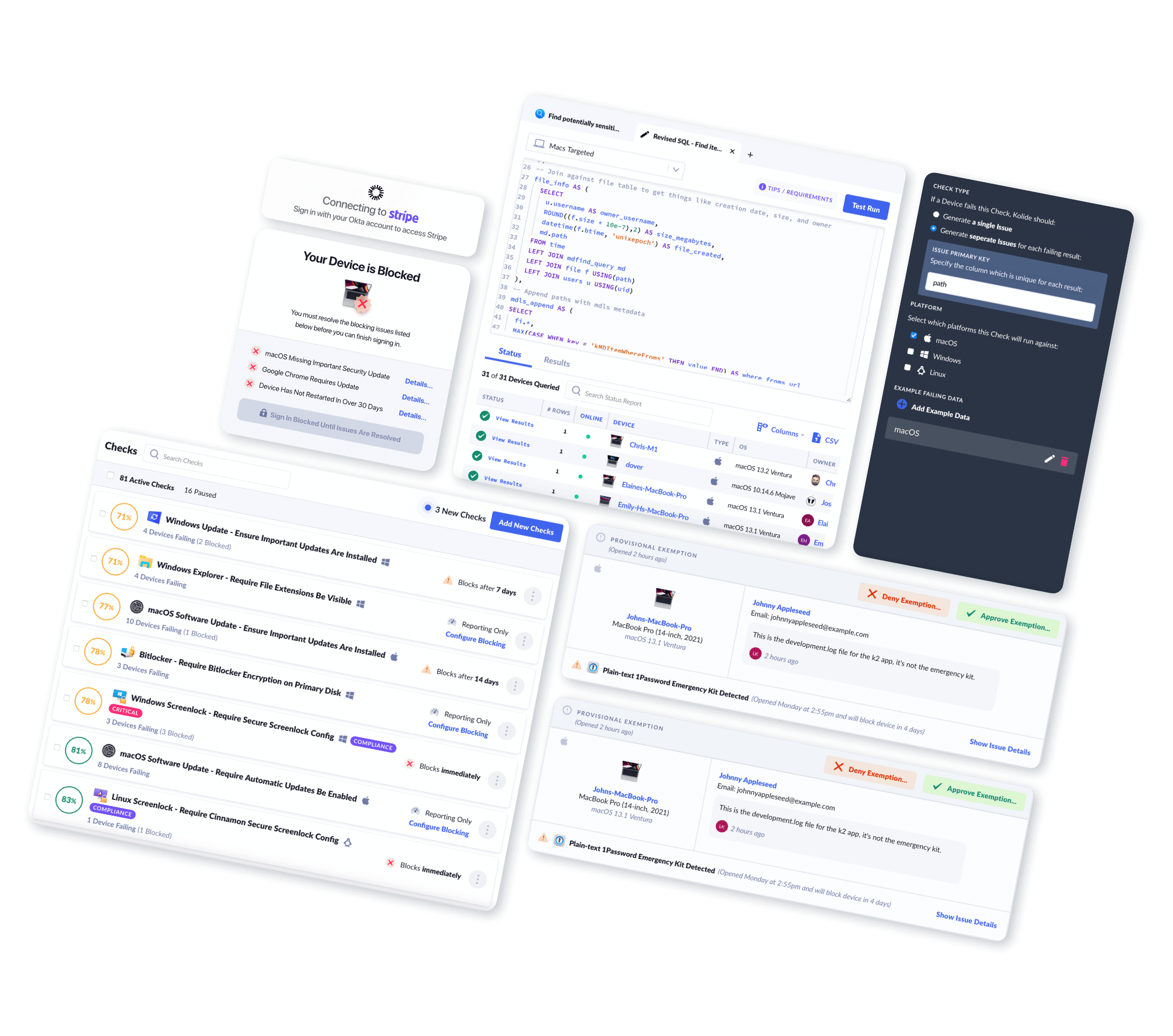

There is an added benefit which is that given Full Disk Access, Kolide catalogs the TCC permissions on a device and can report which devices have extended privileges for various applications. Administrators can then audit which devices have problematic or overreaching application permissions.

Granting osquery/kolide Full Disk Access

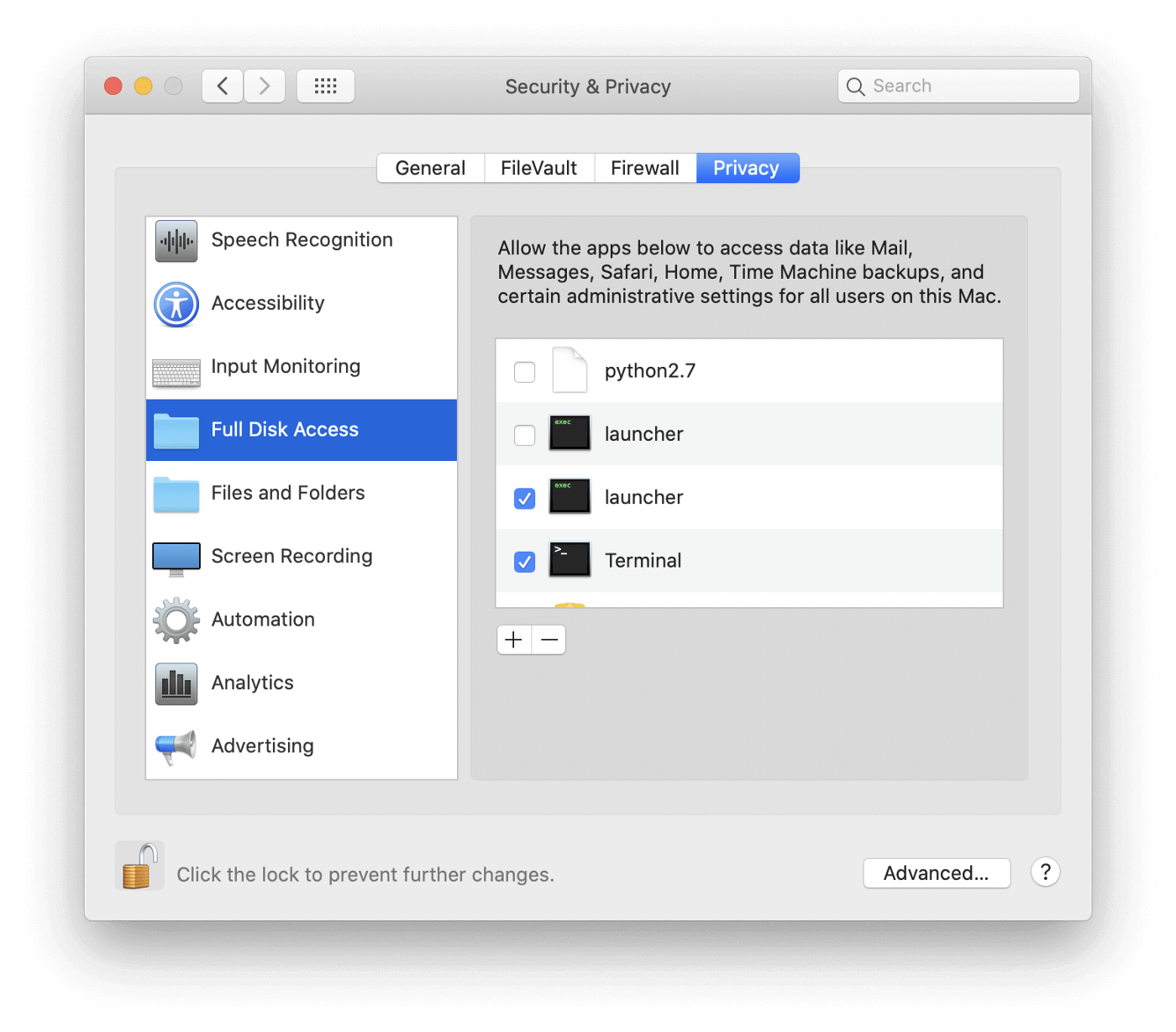

Full Disk Access is the only Privacy scope which will not prompt users to grant permission when an application requests it. This means rather than relying on your application, osquery agent, Kolide launcher to request permission, users have to explicitly grant permission on their own via the GUI. Doing so is relatively easy and is documented for Kolide users in our Support Documentation:

Open System Preferences

Click the Security & Privacy icon

In the left-hand pane scroll down to Select Full Disk Access

Click the Orange Lock icon in the bottom-left corner of the window to enable changes

Provide your password

Type

Command+Shift+Gto open the “Go to the folder” dialogueIf using Kolide’s SaaS service: paste

/usr/local/kolide-k2/bin/launcherand Click “Go” With launcher selected Click “Open”

Examining TCC Permissions using ATC

Users who are familiar with osquery might be aware of the ATC feature which allows extension of the osquery schema by specifying a SQLite database to expose into a virtual table. If you haven’t heard about ATC before, I recommend taking a look at my earlier blog post: Build custom osquery tables using ATC.

If you already know the ropes of ATC you can find a working config block below:

{

"auto_table_construction": {

"tcc_system_entries": {

"query": "SELECT service, client, allowed, prompt_count, last_modified FROM access;",

"path": "/Library/Application Support/com.apple.TCC/TCC.db",

"columns": [

"service",

"client",

"allowed",

"prompt_count",

"last_modified"

],

"platform": "darwin"

},

"tcc_user_entries": {

"query": "SELECT service, client, allowed, prompt_count, last_modified FROM access;",

"path": "/Users/%/Library/Application Support/com.apple.TCC/TCC.db",

"columns": [

"service",

"client",

"allowed",

"prompt_count",

"last_modified"

],

"platform": "darwin"

}

}

}

This block contains two different tables one for the root and one for the user-spaced TCC.db

Parsing TCC database contents

The contents of the TCC database are relatively self explanatory but we will

examine the schema of the access table below:

service:string

These services are mapped to the various privacy categories. Several of them are aliased (kTCCServiceUbiquity = iCloud, kTCCServiceLiverpool = Location Services, etc.) but we should keep them with their system names in the table because new ones are consistently being added. An example of the variety of entries currently:

kTCCServiceAll

kTCCServiceAddressBook

kTCCServiceCalendar

kTCCServiceReminders

kTCCServiceLiverpool

kTCCServiceUbiquity

kTCCServiceShareKit

kTCCServicePhotos

kTCCServicePhotosAdd

kTCCServiceMicrophone

kTCCServiceCamera

kTCCServiceMediaLibrary

kTCCServiceSiri

kTCCServiceAppleEvents

kTCCServiceAccessibility

kTCCServicePostEvent

kTCCServiceLocation

kTCCServiceSystemPolicyAllFiles

kTCCServiceSystemPolicySysAdminFiles

kTCCServiceSystemPolicyDeveloperFile

...

client:string

- This is the domain/bundle_identifier of the application asking for permissions.

allowed:boolean

- When an application requests escalated privacy permissions a dialog prompt is displayed to the user who can choose whether to allow or deny the application. Afterwards, the app persists in the Security & Privacy preference pane GUI under its respective section. If the app was denied it has an empty checkbox (mapping to 0). If it was allowed it has a checked checkbox (mapping to 1).

prompt_count:integer

- An application can issue a prompt more than once asking for elevated permissions. We can track this information and display it to look for potential abuse of TCC requests by malicious apps (an app asking repeatedly for escalated permissions)

last_modified:integer

- The last time the application’s privacy permissions were changed. We can use this to see when a specific action was taken with regards to escalating or deescalating permissions.

Where are we headed?

It stands to reason that Catalina is not the last step in Apple’s overarching push to protect user’s privacy. We can expect that this initiative will continue to further sandbox applications and reduce their cross-system visibility into other processes / files (except where explicitly permitted). With the precedent established, these future changes should be less obtrusive.

In the meantime, we will have to momentarily suffer through Windows Vista-level post-OS upgrade hassle: