Employee Data Privacy: Legal Obligations and Best Practices

In the security world, we talk a lot about what companies should expect from their employees: how to ensure they’re complying with your password policies, working only on approved applications, and handling data responsibly.

But, thanks to new data privacy legislation, this is a good moment to start thinking about what employers owe to their employees when it comes to data security and privacy.

There’s one big development driving this conversation: In January, the “employee exemption” of California’s data privacy law* will expire. That means that employers who meet the law’s requirements will have substantially increased obligations to their California-based employees.

CPRA’s biggest new requirement is that employers provide workers with a detailed privacy policy that discloses what information they collect about them and why. And that’s a conversation that frankly, a lot of companies are not ready to have. (A desire to avoid this conversation is probably why so many companies held out hope that the employee exemption would be extended, and are now scrambling to figure out their compliance obligations).

As a security company whose entire ethos is based on transparency and informed consent between employers and workers, we have a lot of practice in communicating with end users about privacy and security. Here, we’ll help you prepare to have the same conversations so you can obey the law and earn your employees’ trust.

*Confusingly, January 2023 is also when the law’s name will officially transition from CCPA to CPRA. To keep things simple, we’ll refer to it as CPRA going forward.

The Challenges of Addressing Employee Data Privacy

Most employers don’t want to be evasive about their data collection policies; it’s just that achieving transparency is tougher than it sounds. There are plenty of legitimate reasons why companies struggle to talk to their employees about how their data is being handled.

To name a few common scenarios:

- Only the IT and Security teams are fully aware of what a company’s data collection capabilities actually are. (Not only that, in many companies, those capabilities are constantly changing. Without clear processes to keep track of them, understanding quickly falls out of date.)

- Companies can’t guarantee the security of sensitive data, since they have few ways of tracking it once it disappears into a downloads folder or onto unauthorized devices and applications.

- Companies have potentially alarming monitoring capabilities they don’t actually use, or only use for specific, security-related purposes.

Many companies will try to camouflage these issues by writing their privacy notices in vague legalese and burying them in the middle of a pile of onboarding documents, which employees are likely to sign out of a desire to make a good first impression. But this approach is not only out-of-step with the current generation of laws, it creates an atmosphere of confusion and paranoia that drives employees to use Shadow IT just to escape surveillance.

So let’s be clear: The only way to meet your legal obligations and avoid alienating your employees is to be as transparent as possible about data privacy.

Employers’ Legal Obligations for Employee Data

California’s law is just one of a patchwork of international and state-level attempts to enforce data privacy. Not all these laws apply to employee data, and there are notable variations between the ones that do. (For example, New York, Connecticut, and Delaware merely require employers to notify employees about digital monitoring, while Hawaii goes further by prohibiting employers from tracking location data on an employee’s personal mobile device.)

We’re going to devote multiple articles to data privacy legislation (subscribe to our newsletter if you’d like to read them), but for now, we won’t get too deep into the fine print of any specific laws. Instead, we’ll focus on the common thread between the existing and pending laws: their emphasis on transparency.

Few US laws–at least at present–do much to ban specific types of data collection or monitoring, but they do demand that employees are made aware of these practices via a detailed privacy policy.

Unfortunately, even the words “detailed privacy policy” raise as many questions as they answer. How detailed does it need to be? Should employees consent to it during onboarding, or at every point where their data is being collected? And what does “consent” mean when we account for the uneven power dynamic between employees and employers?

Even CPRA is frustratingly short on these details. The law was written with consumers in mind, and doesn’t have a lot of employee-specific language, though it does claim to “[take] into account the differences in the relationship between employee…and businesses, as compared to the relationship between consumers and businesses.”

At this point, it’s too soon to predict how regulators and judges will interpret the CPRA as it pertains to employees.

What we can do is speak more generally about the spirit of this and other laws, so you can craft an approach to your employees’ data privacy that aligns with the evolving expectations of regulators and your workforce.

How to Create An Employee Data Privacy Policy

Until now, employers could get away with addressing employee data privacy with a few words buried in an employment contract or annual email. But new laws require much more thoughtful and detailed documentation, written to be understood instead of just to manage liability.

Make a data inventory

For employers, step one in this process is getting clear on exactly what employee data you currently collect. That’s easier said than done, since that information is spread across multiple teams. HR has sensitive employee records, Security and IT typically have expansive powers to look at employee devices, and management may have the ability to track employees via “productivity software” or messaging apps.

You’ll need the participation of all those departments to get a comprehensive picture of what data you have, how you’re securing it, and how long it’s being retained.

Explain the purpose of data collection

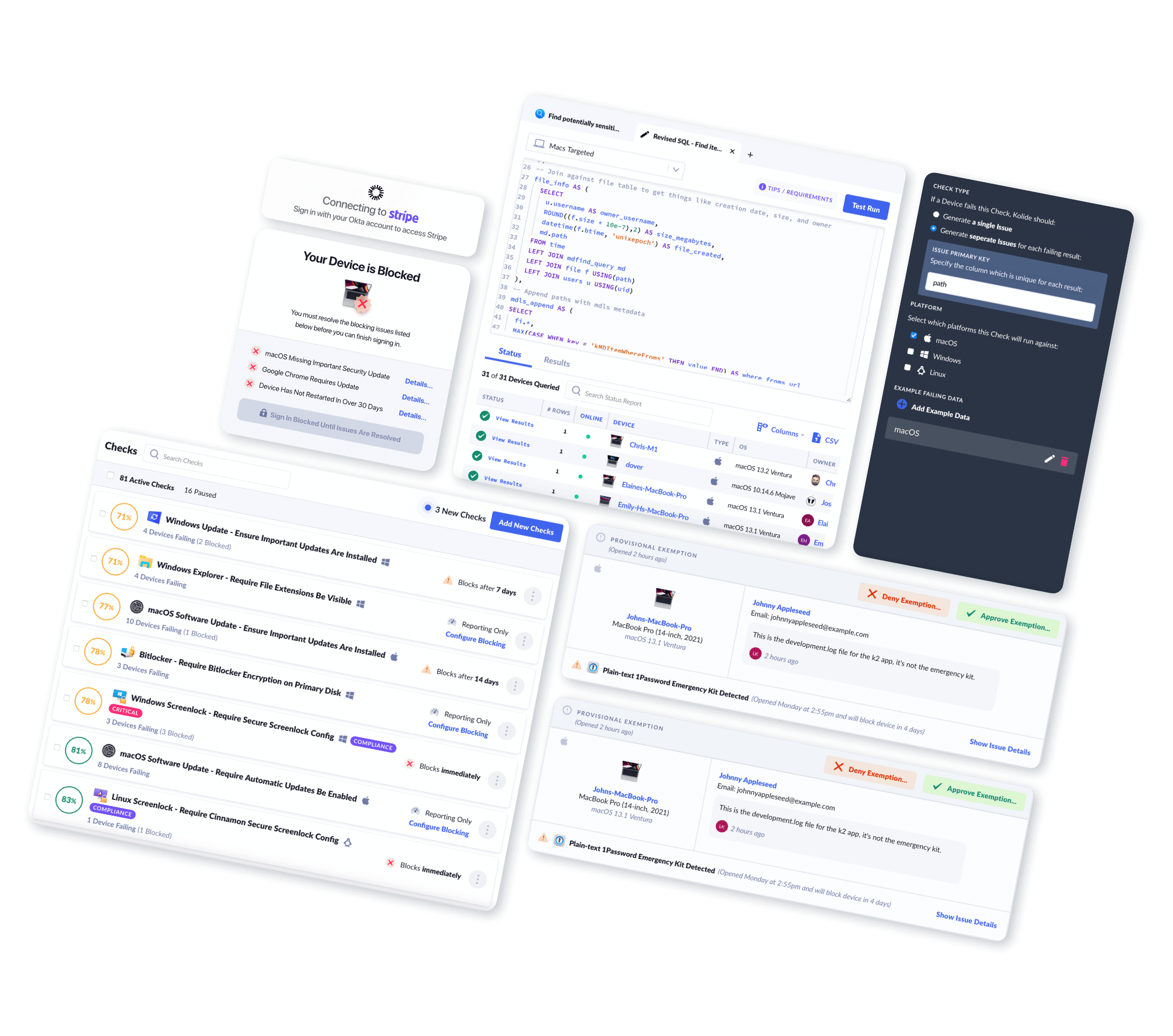

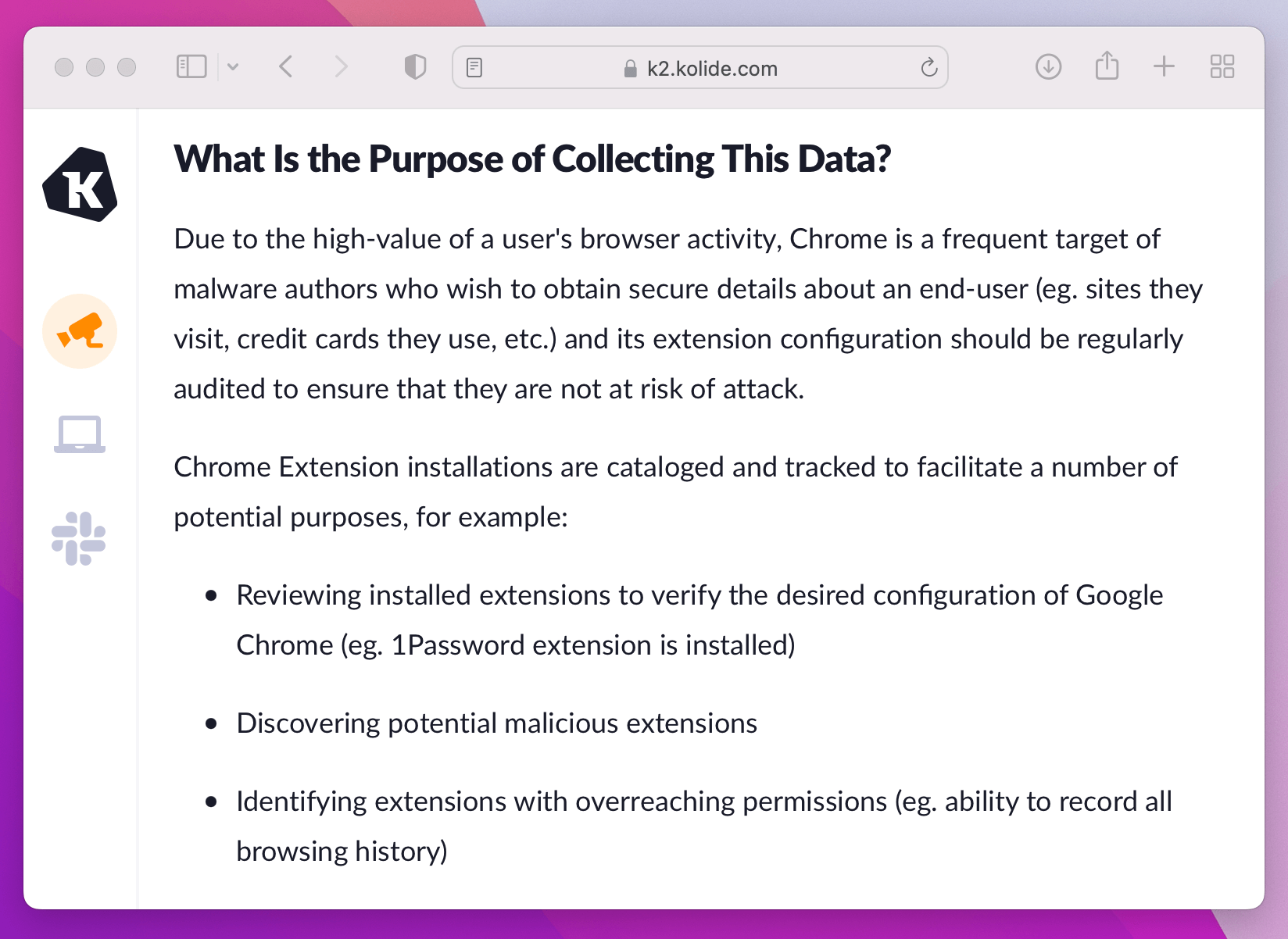

Once you understand your own data collection capabilities, it’s time to explain the reasoning behind each one. This is something we have a lot of practice with at Kolide, because our product monitors employee devices to ensure they’re compliant with security policies and best practices. But–unlike many other endpoint security tools that operate invisibly–we’re transparent with end users about everything we collect and why, via our user privacy center.

So, for example, if a user wants to know why we monitor Google Chrome extensions, they can read a detailed article that explains what those extensions are and why we track them.

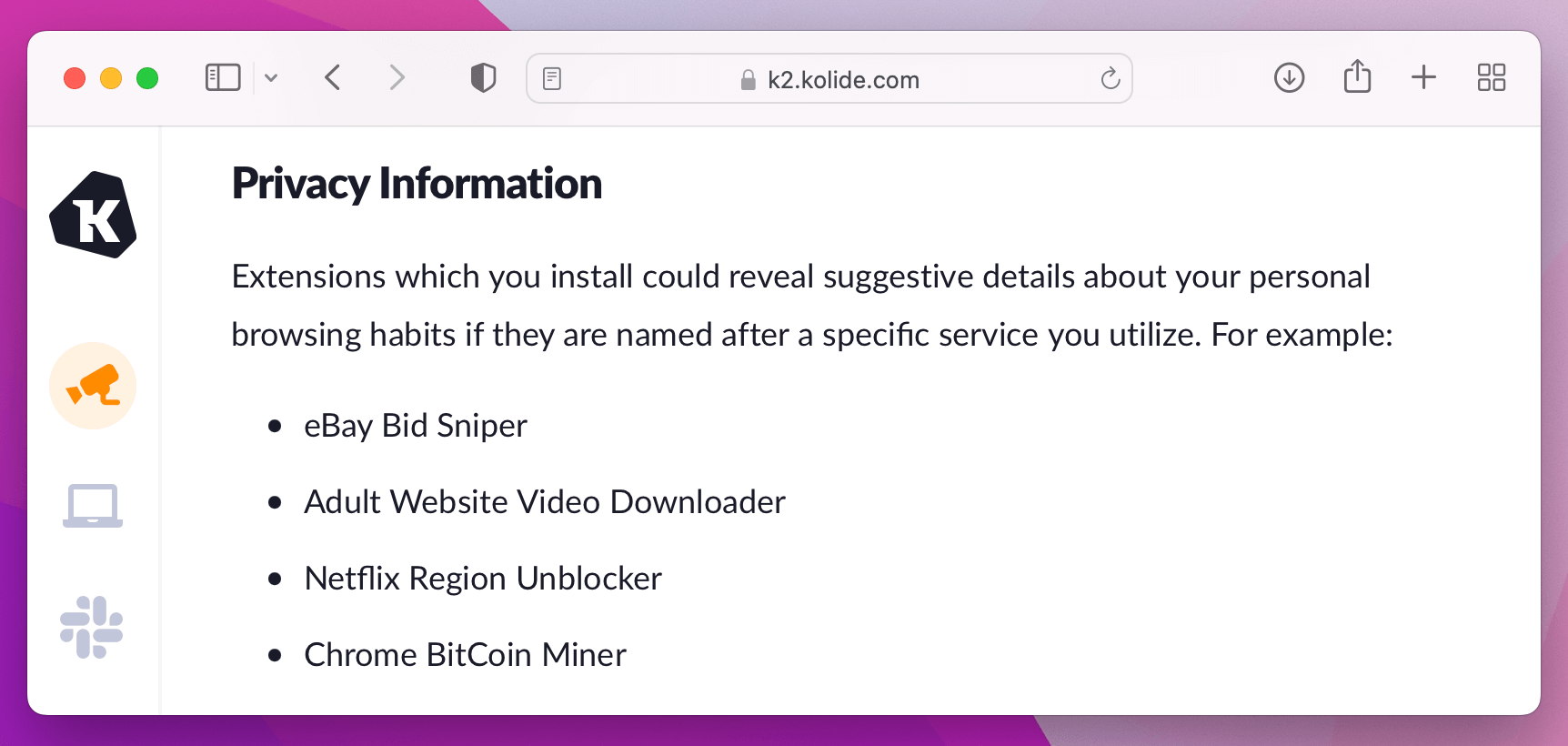

In addition, we explain the potential privacy risks of all the data we collect.

The goal here isn’t to eliminate every form of sensitive data collection, but to contextualize and explain the risks. That way, users can make informed decisions about the kinds of behaviors they feel comfortable doing on a work device.

In addition to the data that has a clear and defensible purpose, you may also have some capabilities that you would only use when absolutely necessary. For instance, many security and monitoring tools can track the location of a given device, which can make users feel overly surveilled. In cases like that, your employee privacy policy should explain that you would only use geolocation data in specific circumstances, such as to track down a lost or stolen device. (And then, of course, stick to your word.)

Perform a privacy impact assessment

In the course of documenting your approach to employee data privacy, you’ll likely come across some practices that fall in a gray area of ethics, legality, and simple necessity.

For instance, IT might want to collect the names of very large files on a computer in order to decide whether they can be deleted if the user is running out of disk space. The goal is innocuous, but there’s always a chance that one of the files is named something like “divorcelawyerbillings.zip.” In such ambiguous cases, it’s a good idea to follow the lead of GDPR.

Under GDPR, employers can collect data if it serves a “legitimate interest,” but to prove such an interest, they have to conduct a privacy impact assessment. As the Dickinson Wright Law Firm has written, “this must be documented to demonstrate that the employer’s legitimate interest does outweigh the employees’ rights.”

Privacy Impact Assessments, and their close relatives, Data Protection Impact Assessments, are commonly used by government agencies, but any organization can adapt them to their needs. What matters most is that your employees are confident that you have carefully considered your policies, instead of just grabbing whatever data you can.

Present documentation and respond to feedback

When you’re ready to present your policies, there are a few things you can do to ensure it lands well.

One thing all the recent employee data privacy laws agree on is that a notice of collection should be conspicuous. That’s a little tough to conceptualize in a remote work environment, but our approach to it is to include a link to the privacy center in every end user interaction. As our CEO has written, “informed consent should take place in moments when there’s a chance lack of consent could damage the trust between the end-users and the security team. An example of a situation where consent should always be obtained is the deployment of software that collects facts about user devices.”

Another common stipulation is that notices should be written in plain, accessible language, and not simply cover all collection practices by informing employees that they have “no expectation of privacy.” Again, our privacy center is written with a non-technical reader in mind. (We also have a separate user privacy policy that is more legalistic, but we don’t try to make one document do double-duty.)

We’d also add that, as much as possible, your privacy policies should be universal, so you don’t have one standard for California workers and another for everyone else. Your company might have state-specific privacy policies for consumers, but consumers are unlikely to compare notes across state lines, and your distributed workforce certainly will.

Finally, we advise you to invite feedback from your staff. Workers may have questions about why certain practices are necessary, and you should be prepared to defend (or reconsider) your choices. If you simply issue an announcement full o f potentially alarming information, and don’t create a space for workers to ask questions about it, you’re inviting confusion, anxiety, and dissent.

Being Transparent About Employee Data Privacy Benefits Everyone

There are security professionals (not to mention lawyers and CEOs), who think of increased data privacy obligations to employees as an onerous burden. They argue that employees should already know that their workplace has the right to whatever legal data collection it sees fit. Furthermore, they’d say that if you’re not doing anything wrong, you have nothing to hide.

But that mentality doesn’t reflect the reality of working life. For one thing, the line between the personal and professional is only getting blurrier–we check Slack on our personal phones, shop online with our work computers, and our families play in the background of our Zoom calls. Rather than pretending this reality is a failure on the part of employees, workplaces need to account for their access to private information, and limit it as much as possible.

Another argument in favor of transparency is that confusion about data privacy is making employees miserable. In a recent survey, 59% of employees reported feeling stressed and anxious about workplace surveillance. The same survey found that employees hugely underestimated the amount of surveillance taking place. For instance: only 19% of employees suspected their jobs of real-time screen monitoring, but 53% of employers reported doing it. Hiding this problem is not the same as solving it.

It’s past time to shine a light on this subject, and the experience doesn’t even have to be unpleasant, so long as your policies are ethical. But you should start having these conversations now, on your terms, instead of at the point of a sharp piece of legislation.